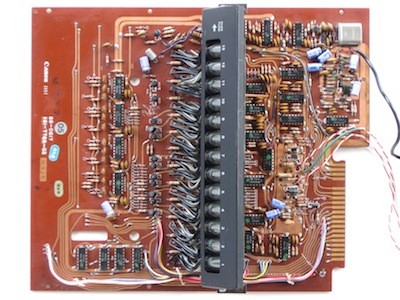

Upper board, component side.

Notice the crystal in the upper-right corner of the photo.

Generally calculators didn't require the timebase precision provided by crystal oscillators and instead got away with simple RC astable flip-flops for the master clock.

However for calculators using acoustic delay-line memories, master clock precision was needed to keep the clock rate synchronous with the delay-line pulse velocity.

Another method of maintaining sync was to use a bit pattern in a channel-slice of the delay-line to set up a phase-locked-loop that tweaks the master clock rate with drift in the delay-line.

|

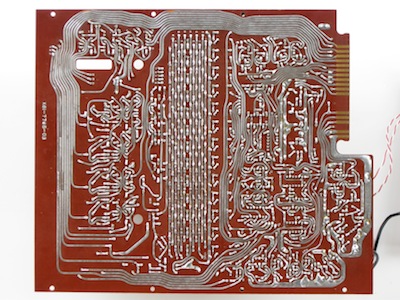

Upper board, solder side.

|

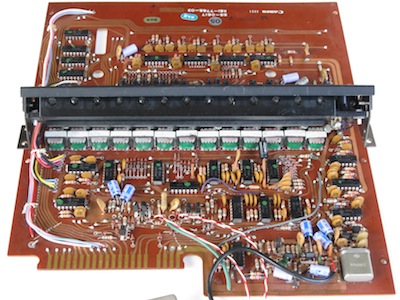

Upper board from the rear.

The pulse transformers are for high voltage isolation of the Nixie anode drivers.

|

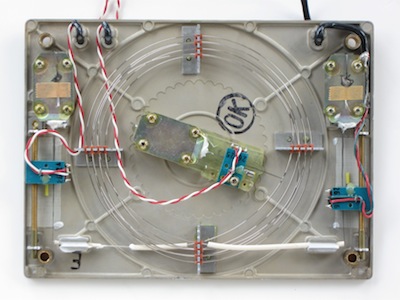

The delay-line from below.

Opening the delay-line requires drilling out the brass rivet flanges on the 4 mounting spacers.

|

Inside the delay-line.

This is a torsion-mode delay-line. The transducer solenoids are in the blue housings.

The flat metal tapes going through the solenoids in those housings are the actual magnetostrictive material.

The delay-line proper is the coil of wire mounted in small rubber bushings for acoustic isolation from the frame.

The tapes are spot-welded in tangent to the circumference of the delay-line wire.

The magnetostrictive contraction and expansion of the tapes, by the solenoids, thus torques the delay-line wire.

The read transducer is on the right. The first write transducer is on the left.

The transducer in the middle is the second write transducer, used to achieve the 'register slippage'.

The delay line wire is 6 loops of ~ 91mm diameter.

With an ends and the tapes, the total length of the line is:

6*pi*91mm + 2*65mm + 30mm + 20mm = 1895mm

The delay is 635µS.

The pulse velocity then is:

1895mm / 635µS = 2.98 Km/S = 10740 Km/h

The registers present a storage requirement of:

5 registers * 16 digits/register * 4 bits/digit = 320 bits

A few of the 320 bits are provided in flip-flops, and with some other adjustments for the details of the implementation,

the delay line provides 317.5 bits.

Thus each bit occupies:

1895 mm / 317.5 bits = 6.0 mm

of length in the delay line.

|